Mongolians understand their place in life which, for females, is responsibility for everything inside the ger (also known as a yurt in other strange places) and the milking. There is plenty of that so they do get outside a fair bit. Men are in charge of all the outside stuff mostly related to stock management and discussing important other things like prices , but women get all the money earned. This division of labour specifically applies to 40% of the 2.7 million population who are nomadic herding farmers, but it also applies to village and city people as in most cases there is no more than a generation of removal from their living in the nomad world. Therefore Kay will write about inside the ger and I will deal with outside.

I organised our Mongolian trip through a local agency and we were provided with a husband and wife team of Nasan and Tuyu, the later being the guide and in charge of inside stuff and she spoke pretty good English. Nasan was the driver and owner of our 1998 Land Cruiser which was immaculate and never missed a beat in 10 days. He knew a bit of English but was reluctant to try when his wife was around. They were wonderful and I was happy to pay the exorbitant tip the agency suggested because they did a great job and looked after us like we were their grandparents.

Mongolia is a democracy following a peaceful revolution in the early 90’s although there is not a great deal of respect for those in charge who, I gather, are the elite and corruption starts from the top here. On our first day we were battling through the horrible traffic in the capital, Ulaanbaatar, where half the population lives, and there was a complete stop of movement because some one important was having a drive through town. When the large black car and outriders swept past the locals all made very sarcastic noises with their car horns which I suspect was not by mistake. The big industry is coal mining, not a good place to be now, especially when their trade is mostly with China which has stopped importing coal. They have other minerals the most important of which is copper and there is a huge big mine that has been some years now getting started and it is supposed to be the financial saviour of the country. Unemployment is currently high and there seemed to be a lot of big trucks parked up. But they have a safety valve for economic problems and that is agriculture.

It would have been good to have had the agricultural correspondent with us but he was otherwise engaged being luxurious in some couth part of the world. So I will just have to try hard to explain what happens in Mongolia. We have to start with land ownership because it is the basis of all economic processes. Everyone is entitled to a small plot of free land although you can’t ask for a specific one (unless you know some one who has influence and an unexplained pile of assets) and for most people, including just-born infants, this land will be near their village or city. For the nomads it is usually their winter camp which has sort of permanent stock shelters. These bits of land are mostly fenced and don’t amount to much in terms of area in the country. Then there are national parks of which there are a few, and then there is everything else which is owned by everyone and can be used by everyone and there are no boundaries and no fences and the only trees are on the steep non-grazable parts. It is one vast, wide open space with big plains, low rolling country and some not too precipitous mountain areas. In other words it is the steppe. So anyone who can get a few animals together and find a ger can set up camp and be a nomad.

Nomadic life here is not quite what you would think because they move between two main camps usually no more then 30 kms apart and often a lot closer. The winter camp is sheltered from the northerly winds as it gets extremely cold, and summer camps are near water supplies and somewhere the breeze can lower the hot temperatures. They live in a ger which is round, about 6m in diameter with one low door and no windows apart from the opening in peak of the roof. All the family lives in this building so as you can imagine they are very compact with what they have inside. The toilets are 3-sided flimsy things with no roof, a long way from home – say 50-70 metres and could be described as rudimentary. I did see a tin bath so presumably they can have a wash once in a while. We spent visiting time with 3 families and had 2 nights “living” with a family at a homestay where thankfully we had our own ger, but no ensuite facilities. Livestock are sheep and goats which run together because sheep are stupid and need goats to lead them, cattle, yaks, horses and camels (2 humps) in combinations that suit the nomads and land conditions. A good ewe is worth US$80, a cow $400 and a camel $750. I never got an answer about yaks. All are milked and the magic herd total that signifies wealth is a combined 1,000 head. The only technology they use are 2 poles in the ground for breaking-in horses. No machinery apart from motor bikes. Dogs are for warning about bad people and wolves, and rounding up stock takes several people on horse, bike or foot. I doubt anything about the operations of this range life have really changed in hundreds of years, apart from mobile phones which make finding out where missing stock are much easier. An example is from our homestay visit when in the evening it was time to separate the calves from the adult yaks so the later could be milked in the morning. The calves were put in a sort of rackety pen made of 4 gate-like things tied together with leather straps. Then everyone milled about trying to catch the calves while a few horsemen lurked in the distance to return the animals that didn’t want to be caught or stay and watch the action. A few metres of wire netting set up in a right angle would have made it all a lot quicker and easier. No one has ever heard of a mechanical shearing set up let alone a portable one and hand milking is how it is done. All of which is the main attraction. These guys are a living, viewable anachronism and they are very welcoming in a reserved way.

Our tour also took in other sights and worthy things like a couple of museums; several Bhuddist places including one that took 3 hours of hiking up and down to get to where the highlight for me was Tuyu and I having lunch with the only monk in his ger; the country’s biggest waterfall that would not get a mention in NZ; and best of all a huge stainless steel sculpture of Chiingis Khan, possibly known to you as Ghengis. Not much really but we only saw the central part of the country and really it is the land and the nomads that are the highlights.

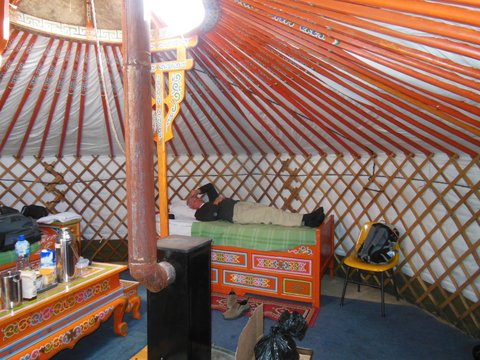

The roads were a hoot. There are sealed roads between the major towns of which there are not many, and once you leave those roads you are on dirt tracks. Didn’t see any metalled roads. Even when we went to a hot springs tourist place with lots of camps and accommodation there were just tracks across the steppes and over the hills. Naturally each driver has their own idea about the best way to proceed so there are usually a wide range of tracks to choose from, or you just start a new one. Nasan loved it. We met only 3 bridges off the sealed roads and one was spectacularly busted, and the other two were of the “passengers walk across before the car” variety, so we just cautiously forded all the waterways we came to. The weather we had was unseasonally cold,with times of snow, hail and freezing wind from Siberia all which added to the fun of open country driving. It also made visting the open air toilets somewhat uninviting and helped when we had 4 days with no running or heated water, because no one sweated. Our accommodation outside of Ulaanbaatar was in gers and I liked them – they make excellent roomy and warm accommodation as long as you keep feeding the stove. The slightly unreal thing about living in a ger is the divide between out and in. When you are in with the door closed it is dark and there is no connection with the outside given no windows. Then you bend down and go outside and you are immediately in the farm with no porch or path to the gate. Just straight into the huge big outside.

Kay’s turn:

Before we got to experience a ger we had a day in Ulaanbaatar where we could access google and go to a concert. Magnificent!! We were treated to throat singing, traditional dulcimers, hearty ballads and a contortionist for good measure.

Next morning we headed off for the first ger visit but it was so darn cold even our hosts would not venture outside for a scheduled camel ride but were content to watch us eat the hotel packed lunch and, with Tuya translating, ask about farming in NZ. Being springtime, the tourist season was just starting and we were amongst the first to arrive. It was 3 hours driving 180 km to the Sweet Gobi Ger Eco-Camp which hadn’t quite got itself into gear but our thickly felt-lined ger was ready with a goat dung fire but no heating in the dining room. Have you ever tried eating with your hands in your pockets wearing 5 layers on the top and even golf wet-weather pants over the lower layers? It was candlelight only in our ger but we got the thermometer up to 38 degrees so there’s a lot to be said for good goat dung. Next morning we clambered into our Cruiser still wearing 5 layers until the vehicle warmed but happily heading for 2 nights at Tenskher Hot Springs with steaming pools to look forward to. Enroute we had the compulsory monastery visit. It was under renovation and all the wooden carved features from 1600’s had been taken down for refurbishment and, it was covertly revealed, could be quietly purchased if the guide could please secrete it up her jacket until we left. Nice little earner for the workmen.

With snow gently falling for part of the trip we took 4 hours to drive 260 kms which was plenty of time for Tuya and Nasan to present D with questions as to how to go into the tourist guiding business on their own account. The mentoring continued until we arrived at the not-Hot Springs. It seems there was a rather obvious problem with the spring only dribbling. This was log cabin-style lodge accomm with a room for us upstairs. Maybe it was the height from ground level but no water could make it up that high to our taps nor to our toilet so there was an expressionless young lady detailed to intermittent bucket brigade. Late that night there was a warmish outside pool available so I plonked in wearing a fair number of clothes that needed washing and as the little snowflakes fell around us we lolled about to the amusement of builders working well into the night on the lodge extension. The owner of the establishment was a bulky, jovial retired wrestler who rocked up the next morning with his bone-crushing handshake. He would have been just the man for dealing with 2 carloads of Mongolians who had pulled up at 1a.m. demanding hot water and food or they’d shoot the pregnant hotel manager. There was no food, there was no hot water and, fortuitously, there was no shooting just a lot of yelling.

We walked 4kms the next morning to visit a nomad family who welcomed us traditionally with warm yak’s milk, a snack of bread with clotted cheese and an offering from the snuff bottle. Apparently the conversation was about their intention to venture into homestays with special reference to the toileting requirements of visitors. Later in the day I trudged to a neighbouring “resort” to have a shower as there would be no likelihood of such things for several more days. There would also be no electricity for lighting or charging devices.

In China I had tried, without success, to buy velcro to mend the handle on D’s bag. Tuya knew just the very place to get it at a “blackmarket” in a small town so when we stopped off for that she was insistent that I also buy some fabric for a child’s garment. She’d seen me knitting (first tourist ever) so thought that at our ger homestay The Lady would show me what to do. Somehow I couldn’t quite see this as a good idea but went along with it. It turned out that The Lady of the family who was hosting us had a household (rather, gerhold) of herself, husband, a visitor who seemed interested in the daughter, 3 almost-adult children, a 2 year-old and a baby and just 2 beds. (I suspect we had the usual 3rd bed in our ger). She had to get up early to make the fire, boil up milk to make yoghurt, seive the cottage cheese, feed the baby, sweep out and make breakfast bread for everyone. Then it was yak-milking time (I helped with that) before more boiling of milk, feeding of baby (who didn’t have any form of diaper – don’t ask) and soup making. Tuya couldn’t see what my problem was with expecting her to fit in a few hours sewing. So in due course I was summoned to the family ger with my fabric, the hand-operated sewing machine from the 1930’s was set on the only flat space and, using a piece of soap, The Lady traced around an existing child’s deel (pronounced dell). That is the outer layer that everyone wears. No pins, just place the fabric under the machine needle and go for it. The iron was needed but with few places to look, it became obvious that the neighbour had not returned it. A son was despatched on the motorbike and he returned victorious with an old electric iron from which the surplus electric cord had been cut off and he quickly placed it on the top of the covered fire to heat. It wouldn’t get hot enough to do the job so I suggested that if I held the fabric against the burning hot chimney and pressed with the iron it wouldn’t need to be hot. Not sure how Tuya translated that but everyone was suitably impressed with the solution. There were a few snowflakes or hail coming in through the chimney gap in the roof landing on my head.

A small family arrived on a motorbike looking for their goats so they too crowded into the ger and there were now 17 of us. They left before the evening meal – primarily a tasty boil-up of goat, potatoes and carrots. They eat a terrific amount of meat and milk product with a few purchased vegetables. They can’t have gardens because the roaming animals would ruin it and they would probably be moving camp before any harvest.

That night it was so dark, it hailed, the wind got up, the temperature dropped and the distance to the plastic-walled shortdrop seemed to double. The Kapiti ice cream container no longer held the medical kit.

A couple of days later we were in international departures at Chenggish Khaan airport, Ulaanbaatar (cheapest duty free perfume in the world) and as I looked out at our plane I commented that my bright orange suitcase had not appeared to be loaded and I couldn’t vouch for D’s either. However, one must trust the system and as we were transitting through Beijing to Shanghai perhaps they had been given special treatment. “Special treatment” is right as they finally rocked up 20 hours behind us.

And now we’re back where we belong.

Until next time…..

Dennis and Kay

zz

The chimney is the hottest part

Machine from Great grandmother

Yak milking

Getting ready for the tourists

Snow outside, 38 degrees inside

Chenggis, Kay and Dennis